|

: Cult Books |

| What makes a cult film? Particularly a British cult film? The websites devoted to "The Wicker

Man" - a film made over 30 years ago -still get 75,000 hits a week; fans of the Italian director Antonioni's

evocation of Swinging London in "Blow-Up" in 1965 still go to the park where the cameraman ordered the

grass to be painted a particular shade of green; devotees of Mike Hodges' 'Get Carter' lobbied the local tourist

office to put the locations of various cinematic murders on the map. Cult equals meaningful. Memorable. Non-disposable. It sticks in your mind. In your heart. In your soul. All cultists create their own pantheon. Cult equals obsessive. |

||

| It's not surprising that in Ali Catterall and Simon Wells' excellent study of cult pictures ('British Cult Movies Since the 60s: Your Face Here') that they are British cult films, dating from 1964 onwards, for it is a truth hardly ever acknowledged by the mainstream that the system of UK government support (effective support) ended with the advent of Mrs. Thatcher to power; and that the studio system which created all of the best British directors (Hitchcock, Lean, Reed, Powell) effectively ceased to exist in the mid-1950s. The Americans, induced by Beatlemania and swinging London, pumped money in during the 60s until they saw that British films lost money. Again and again and again. | ||

| It is a curious fact that it took an Italian to capture the cult of mid-60s swinging London: Michelangelo Antonioni in 'Blow-Up' (1965). Antonioni's style (he is still at work at 89) has divided both critics and his fellow directors. He was Andrei Tarkovsky's (see article TARKOVSKY) favourite European director, for example. Yet, for no less than Orson Welles, the Antonioni style was very laboured, as he told Peter Bogdanovitch: |  |

|

| "I don't like to dwell on things. It's one of the reasons I'm so bored with Antonioni - that belief that, because a shot is good, it's going to get better if you keep looking at it. He gives you a full shot of somebody walking down a road. And you think 'Well he's not going to carry that woman all the way up that road? But he does. And then she leaves and you go on looking at the road after she's gone." | ||

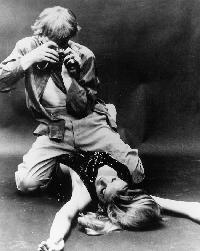

| For the apostles of the long shot, though, Antonioni offered an abundance of lessons. In 'Blow-Up' he transformed

the Woolwich Road area in South London in to a scene for a mysterious 'whodunit?' that was also a 'whydunit?' and

'did anything ever happen at all?' The nature of existence - of reality and perception - is explored throughout the picture. Or rather presented. Emotions are almost non-existent. Interestingly 'Your Face Here' suggests that the film mirrored the director's own cool approach to people in real life. The central character - the photographer based on David Bailey - was originally to be played by Terence Stamp, with his girlfriend to be played by his real-life girlfriend the model (rather than actress) Jean Shrimpton. Yet only two weeks before the shoot started the Assistant Director informed the actors by phone that they'd been dropped. A furious Stamp said at the time: "He might have treated me to a cappuccino and told me to my face. I never saw Antonioni again. There was not a word of apology or anything". |

||

| Perhaps the director simply decided that (in Ms. Shrimpton's case) models can't act. Or maybe he became aware that

for the atmosphere he wanted to create, and to create a picture that would last, 'celebrity' actors were a distracting

irrelevance. The film shoot was 5 weeks. The script 32 pages long. The actors never had a full copy of the material and would simply receive their lines for the next day the night before. Its vision of London in 1966 is still intriguing today: it creates a state of mind. |

||

| Reactions to the film were - in the best cult tradition, as cult pix are not Steven Spielberg after all - bitterly divided. Alfred Hitchcock privately observed that Antonioni was miles ahead of what anyone else was doing stylistically: it made the Englishman completely re-think what he was doing. Yet American critics reported packed audiences who seemed to hate what they were watching; "almost as if Antonioni had insulted them personally" as one writer put it. | ||

'Your Face Here' does a very thorough

job in detailing the background and whereabouts of the various 'Blow-Up' locations, and does this for all 12 pictures

that it examines. A geographical sense of place is very important to all these British pictures; if London permeates

'Blow-Up' then the grimness of 60s Newcastle is an essential backdrop to British director Mike Hodges' 'Get Carter'. 'Your Face Here' does a very thorough

job in detailing the background and whereabouts of the various 'Blow-Up' locations, and does this for all 12 pictures

that it examines. A geographical sense of place is very important to all these British pictures; if London permeates

'Blow-Up' then the grimness of 60s Newcastle is an essential backdrop to British director Mike Hodges' 'Get Carter'.'Get Carter' has been seen as the daddy of the Guy Ritchie gangland clones, but Hodges has distanced himself from this idea, describing the relation of his film to 'Lock, Stock' as Jacobean tragedy to a Feydeau farce. Based on a novel by Ted Lewis, the film had already been scripted and put together before Michael Caine was cast. The minute Caine was placed Hodges was under pressure to put in other famous actors, and thus unbalance the whole picture. As he tells the book's authors: "They (the studios) started to try and get me to have all sorts of people in the film, which I found completely ridiculous. Caine did jack the film up, away from reality in some ways, because you had a star and the star brings a lot of baggage with him. My next fight was to surround him with unknowns, to help ground the character in the film itself. And I had a real hard fight to get all those pretty well unknown actors at the time to play all the subsidiary roles." |

||

| The (usual, unfortunately) seething discontents of the casting process are revealed in the book; a miserable Britt Ekland ("I don't like men who wear glasses"); a real-life envious hatred of Ian Hendry for Michael Caine that was able to be used in the part. Since its appearance in 1971, 'Get Carter' still stands up wonderfully well, and Mike Hodges definitely places himself in the cult group for his opinion "I don't think anything should be stated obviously…"; perhaps the main difference between the underground and the banalities of mainstream cinema. Despite the subtlety of its approach, UK critics found it pretty offensive; as Felix Barker of the London Evening News put it: "What's that strange smell in my nostrils? … What is this garbage clinging round my ankles? …" | ||

| Reactions to 'The Wicker Man' were scarcely any better yet 30 years later it continues to live on. The picture

is one that has been kept alive by its fan base, and by the opportunities created by video and DVD; its fate in

the 70s was a difficult one. As playwright Anthony Shaffer, who wrote the film's screenplay, told journalists in

the 70s: "The film business - or what's left of it in England - like to play safe. Originals are difficult to get done, and I think it's the fault of those who sell the films and advertise them". Scottish paganism … Virgin sacrifice … The Druids … Pre-Christian Celtic customs that survived in some parts of Northern Europe in to the nineteenth century … A difficult brew to get made, even with Hugh Grant (inside the wicker man, hopefully) let alone Britt Ekland (miserable on this shoot again as the authors tell us). |

||

| The film itself was a victim of its times. By the early 1970s US investment in the UK film industry had dwindled from £100 million to £ 30 million. The only significant films being financed were versions of TV series as well as the interminable Carry Ons. British cinema had become a (bad) joke. | ||

| For film fans the details of the brave production make the unusual sad reading: the actress (Britt Ekland, of course)

who slags off all the locals, leading to press problems; the director (Robin Hardy) so over-worked that he collapses

with a heart attack while editing. Yet probably the saddest thing of all about it is that British distributors

just did not market it properly; screenings had no announcements, no publicity. They were completely out of touch

with their potential audience (26 years before The Blair Witch Project), so much so, in fact, that Christopher

Lee had to ring up all the critics he knew himself - and offer to pay for their seats - to get the picture noticed;

this is what the collapse of the studio (promotional, as well as cashing/financing) system in Britain had done

to British film-making. The trailer made was so bad that it gave away the surprise shock ending (clue: it involves

a wicker man, but not Britt Ekland). It says a lot for the persistence of cult film-makers that, 30 years later, the film is still being reconstructed from its various cut forms. A recent re-release of the soundtrack sold out in 3 weeks. Audiences have become more sophisticated, more searching, more determined to find what they want, especially when what they want is darker, more threatening, more realistic, more unpredictable, than the mainstream. |

||

| All this is well covered in 'Your Face Here', and it's an excellent survey thoroughly worth buying. | ||

|

'British Cult Movies Since the 60s: Your Face Here' by Ali Catterall and Simon Wells © Fourth Estate, 2001, £14.99. |

||

| The recent re-issue of many of the key works of American writer Cornell Woolrich is long overdue. Although most

famous for his original story 'Rear Window' which founded the basis for the Hitchcock film, Woolrich was in fact

far more of a bizarre and dark writer than familiarity with just that one story would suggest. Whereas in Britain

the tame formulas of Agatha Christie were the norm, Woolwich offered his readers a modern gothic descended from

Edgar Allan Poe; horror, the supernatural and crime elements all competing in one bizarre mix. Woolrich always appealed to film-makers; 'The Bride Wore Black' - one of the new re-issues - formed the basis for Francois Truffaut's 1967 picture starring Jeanne Moreau. Truffaut commented: "One thing intrigued me: to make a film about love without a single love scene". Woolrich is the king of the preposterous, the Howard Hughes of pulp fiction. In this novel his heroine is the personification of revenge. Truffaut called her more of a goddess than a character, and in the book she systematically slays a series of suitors. She becomes whatever the men want her to be. She is a chameleon. She can metamorphose from one character to another to suit each victim: the blonde femme fatale; a cute school ma'am; an opera-going vamp; a quivering artist's model; half-naked with her bow pulled back, like Artemis, Diana, the razor-sharp arrow-head poised to slice in to the painter's heart. The heroine finds her victims Achilles heel: she becomes what they want her to be in order purely to destroy them. It is essentially ludicrous, and the murderess herself is ludicrous, hell-bent on a fatalistic task that proves bizarrely mis-placed. |

Ludicrous, yet it works. Woolrich's writing

is like a crazed clockwork machine; often racing to its pre-arranged conclusion despite whatever absurdities will

take it there. It is darkly fatalistic. In one story a victim is told by a fortune teller that he will be killed

by a lion at midnight, and the entire energy of that story is to make his absurd possibility a real fear for the

reader. The seemingly impossible can happen, says Woolrich, and it is happening everyday. Perhaps one of the keys

to his mixture of doom and the ludicrous was an observation he made about his childhood self when he was told by

an adult of his own mortality: Ludicrous, yet it works. Woolrich's writing

is like a crazed clockwork machine; often racing to its pre-arranged conclusion despite whatever absurdities will

take it there. It is darkly fatalistic. In one story a victim is told by a fortune teller that he will be killed

by a lion at midnight, and the entire energy of that story is to make his absurd possibility a real fear for the

reader. The seemingly impossible can happen, says Woolrich, and it is happening everyday. Perhaps one of the keys

to his mixture of doom and the ludicrous was an observation he made about his childhood self when he was told by

an adult of his own mortality:"I had that trapped feeling, like some sort of poor insect you've put inside a downturned glass, and it tries to climb up the glass, and it can't, and it can't, and it can't". And in 'The Bride Wore Black' the goddess swipes her victims like so many flies. 'The Bride Wore Black' by Cornell Woolrich, ibooks, New York, 2001, £7.99, www.ibooksinc.com. Also available 'Phantom Lady' and 'Rear Window'. |