|

: If... |

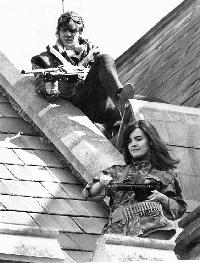

| In his trilogy of films on Britain - If… (1969), O Lucky Man (1973) and Britannia Hospital (1982) - director Lindsay Anderson produced an uniquely thought-provoking series of emotional reactions to the climate of the times. All three films are intellectually stimulating and often very funny, but it is their emotional force that makes them most memorable. Each film reflects many of the different facets of the 60's, 70's, and 80's; they show us the prospect of liberation and its utter perversion. | ||

| If… like so many of the finest films, nearly never appeared at all. Film company executives regarded it as a garbled mess; they could not cope with its inversions of reality. An assassinated chaplain is pulled out of a cupboard to shake his killer's hands; a housemaster's wife wanders nude around the empty school; a general continues giving a speech to parents on school day as smoke wafts up through the wooden floor and chokes them. |  |

|

| The boarding school milieu of the film is presented as tranquil, timeless, self-confident. Yet it is also the home of sexual repression and casual brutality. The three schoolboy heroes are beaten mercilessly in the gym while the camera tracks over the listening younger faces in their dormitory. | ||

| What distinguishes If… from Anderson's later films is its moments of 'Epiphany' as Yeats would have termed them. Sections of the film that glow with menace, with mystery, with a sense of wonder. The revolutionaries escape on a motorbike and meet a girl at a café; the sexual encounter that follows is primitive, animalistic, liberational. The boy and girl tear at each other with their teeth in savage fury. | ||

|

Ordinary events assume a powerful force. The discovery of a foetus in a jar while clearing out a basement room. A schoolboy watching enrapt as another combines power and grace on the parallel bars. | |

| Anderson believed that 'surrealism' had been so widely used as to become meaningless as a critical term. Instead,

since he came to prominence with Free Cinema in the fifties, he often spoke of a striving for 'poetic realism'

in his films. He commented: "When I'm talking about poetry, I'm not talking about the romantic schlock but the work which goes beyond the literal. Work in which the events or things happening have more profound or far-reaching implications or meanings than just the simple event you are watching." |

||

| The rebellion in the school transcends its circumstances; as the revolutionaries machine-gun their scores of enemies from the rooftops, the camera holds Malcolm McDowell's face in a big close-up. The concentration on his face provokes us to focus on our own emotional responses to what we have seen, and, more importantly, what we have felt. | ||

| O Lucky Man although only made five years later, shows a complete dissolution of the nihilistic force of If… The hero of the earlier film (again named Mick Travis and played by Malcolm McDowell) is now plunged into a picaresque series of events. | ||

| He uncovers a man's head that has been transplanted onto a pig's body. It sweats and pants in its hospital bed. He is strapped into a chair and tortured by British Government agents; the tea lady comes in and pours while he screams. Starving and desperate, he enters a church and attempts to eat the Harvest Festival food. A parishioner forbids him as it is "God's food". She gives him her breast to suck as if he were a child. Tried for a crime he did not commit, Travis is sentenced by a judge who in the privacy of his chambers, reveals nudity beneath his robes and is beaten by a clerk upon a table. (Still wearing his wig, of course). | ||

| In this film Travis is the object not the subject of the story. He is carried along by chance and coincidence;

his only motivation is the hope of success. Floating like driftwood he obtains enlightenment at the film's climax

when he auditions for a part in a film and is hit over the head by the director with a rolled-up magazine. Even

his final enlightenment is totally arbitrary. To that extend O Lucky Man reflects Anderson's feelings about the

Britain of the mid 70's, when he wrote: "The British cinema rather correctly mirrors a nation that has ceased to believe in itself, is confused and fatigued, divided and without imagination. In fact, it mirrors a nation in the middle of a nervous breakdown." |

|

|

| What is so interesting about Anderson's trilogy of films is their accuracy as a reflector of the mood of the times. The nearest film to Britannia Hospital (1982) in its mood would be Jarman's The Last of England, a film dramatically different in almost every way in its form and construction. Jarman's film being personalized and elegiac, whereas Anderson's seethes with mob-law, wanton violence and hatred. Yet both films capture the mood of the nation without being egotistical in the way that some contemporary films such as The Ploughman's Lunch and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid were. Both the latter have a very contrived feel about them: an aura of preaching to the converted. | ||

| Britannia Hospital presents us with a mass of people with little in common except intolerance and greed. A human brain is liquidized and drunk in front of a TV crew: a cocaine-crazed TV engineer is murdered by a hate-filled crowd. A dwarf and a transvestite impersonate royal advisers. The Queen Mother has to be smuggled into the hospital to open a new wing disguised as a patient. A group of people are trapped together - like Bunuel's The Exterminating Angel - but there is no sense of any escape through dreams of imagination. All the minds of the characters are pre-occupied with the material and the superficial. Malcolm McDowell's character - now metamorphosed into a TV reporter - is killed and beheaded by a mad scientist who is re-using human parts. A headless naked corpse - blood gushing everywhere - attempts to strangle the scientist before its second death. | ||

| The super intelligent mind-machine that the modern Frankenstein has created closes the film by quoting from Shakespeare:

"O what a piece of work is a man … In action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god." Yet

the overwhelming impression of the film is of claustrophobia, a complete lack of spiritual value, of grubbiness

and dirt. It is the Britain of the tabloids; of industrial unrest; of a divided society lapsing into chaos. The transition from If… to Britannia Hospital is a shocking one; there is none of the magic, of the sense of possibility of the earlier film. There is no beauty in it at all. Any brief sexual encounter is tacky and unemotional. Dreams are redundant. |

||

| Britannia Hospital received a poor critical and public response; the fact that it appeared at Cannes just as the Falklands War broke out, and new patriotism and national spirit appeared, can have done the film little good. Indeed, one might ask what place there was for the revolutionary vision of the original If… in the Britain of the 80's after ten years of Thatcherism? Many of the new accepted beliefs of the 60's had been overturned by the new breed of monetarist revolutionaries. Paradise was postponed. The 60's meant little to Thatcherite youth beyond drugs, sex and mini-skirts. It was no longer remembered as a time of freedom and creativity - only one of aberration and fantasy. Anderson himself pinpointed the change: | ||

| "People are afraid of being inspired … That's the terrible recreation we've suffered from. The 60's were a great period but it seems very fashionable to sneer at them now we've opted for materialism. People that have opted for materialism are a bit defensive really. They are threatened by all the aspiration, irresponsibility and fun that went into the 60's and they have to make out it was bullshit and a complete waste of time." | ||

| Anderson's trilogy of pictures stand as a unique insight in to a process that has become entrenched across Europe: the complete domination of what he defined as 'materialism', something that is always concerned with the surface of things and never with how they really are. | ||