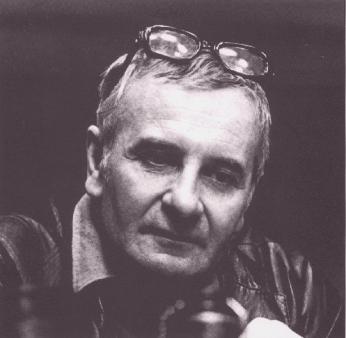

I interviewed Lindsay for a small film magazine before his sudden death in 1994; for various reasons the piece was never published, and I present it here for the first time. His views are as relevant now as they were in the dog days of the Tory area. |

|

| Guy Byrne: | You haven't made a feature film in the UK since 'Britannia Hospital' - why not? |

| Lindsay Anderson: | What my work stands for has become by-passed. A certain independence is no longer valued. What were the 1950s and 1960s about? They were about freedom, and they weren't about profit-making. They weren't about money-making. That started in the 1970s. I was quite aware that that was happening. Now there's so much about getting distribution in America that the whole thought of what you're doing, or what it's about, has practically disappeared. |

| Guy Byrne: | 'Britannia Hospital' presented a view of Britain on the verge of collapse (deteriorating NHS, strikes, slavish adoration of the Royal Family etc.) and did it at the same time as the Falklands War and a patriotic boom that swept Mrs. Thatcher back in to power; were you looking for trouble or was it simply a question of timing? |

| Lindsay Anderson: | It's fatal, I know, to invite people to think. 'Britannia Hospital' itself is extremely complex. All the time it's changing its view. I had a very nice letter from Wajda, the Polish director, saying it was the best Polish film he'd seen for 5 years. I took that as a big complement. In England you put a film like mine on at the local Odeon and it's not what the audience expect a film to be. They've been brain-washed into not wanting to think. Well at least the older people have … Young people are the only hope. |

| Guy Byrne: | Maybe it's not only thinking: a lot of people don't really want to feel either. |

| Lindsay Anderson: | That would lead us on to a huge subject - what I call the flight from emotion. The establishment doesn't want to

be emotionally challenged. And by the establishment I mean the people (cinema exhibitors, broadcasters) who really

control things. That establishment promotes art that hasn't got any real emotion in it. My film may not be perfect - maybe it has too many ideas - but it is not drily intellectual. It presents to some extent a threat. It is subversive. |

| Guy Byrne: | The most enduring films often are. Maybe the only hope for British cinema is from its subversive elements. What do you think of the Surrealists? - you're often compared to Luis Bunuel. |

| Lindsay Anderson: | Influences are very difficult to talk about. They're not necessarily conscious … As for the Surrealists as a movement, remember they were a movement. Artists had contact. At the time of surrealism, artists knew each other. In England now you're totally isolated. In the 1950s when you had a British renaissance in cinema and in the theatre, there was valuable interaction. It's every man for himself now. |

| Guy Byrne: | In the 1950s you were almost seen as a proto-punk movement in the arts - the 'Angry Young Men' - a title stamped on you by the press. How does it feel to be called an 'Angry Young Man' when you're drawing your old age pension? |

| Lindsay Anderson: | (Laughs). They're happy for you to be an Angry Young Man when you're 25,30, 33 … If you persist beyond that, you're

an irritation to the media. They depend on being able to pigeon-hole people. One mustn't expect to learn anything from the press. |

| Guy Byrne: | Very little gets written about the experimental movement you tried to create - 'Free Cinema' - which a lot of anarchists thought meaning not having to pay. |

| Lindsay Anderson: | The biggest problems Free Cinema faced were the English tradition of Philistinism and conformism - and they won out in the end. Today nobody knows anything - the result of television, which has drained people of the power to think or concentrate. |

| Guy Byrne: | Your cinema ideas were very radical for the UK, but they didn't tend to get picked up by the UK press. Why not? |

| Lindsay Anderson: | In the 1970s … the critics tended to take more of an interest in French and German cinema than British. If people don't care about their own film culture, it dies. As EM Forster put it 'only connect'; if you don't have connections you can't develop. Neither critics nor artists. |

| Guy Byrne: | And you're saying that the UK's film scene is one without connections? That there's no infrastructure? |

| Lindsay Anderson: | In today's climate I'm sure I'd never be a film-maker. The last 10 or 15 years have been a disaster. It's very

interesting how the 1960s get slammed at the moment - written of as being all flower-power. It was bloody well

everything. The 1960s were a very fertile period - compared with that, now is as barren as Thatcher. A film like 'If …' couldn't be made today. Today's version would come out like 'Another Country' - very glossy and varnished, no kick or incitement in it. |

| Guy Byrne: | If there is to be any incitement … it would have to be subversive … if there's to be any soul in a film … if you can say a film has a soul … I think we're agreed on that, aren't we? … |

| Lindsay Anderson: | Yes … I think we are. |

© Guy Byrne 2002